I wrote this in May 2007, a year after the May 2006 police riots where they unleashed violence on Critical Mass participants, which led to the formation of Bike to the Future (now Bike Winnipeg), Winnipeg’s first dedicated bike lane, and Winnipeg Copwatch, among other things. I meant to submit it for publication as a Support Local News oped, hence the explanatory commas for the unfamiliar and less-militant tone, but I don’t believe it went beyond an email list (so the police read it, at least 😝)

I’ve made some small edits and added images with 2022-written captions but have otherwise left the various idiosyncracies intact 🥴

What have we learned?

It was a year ago that police response to the May 2006 Critical Mass rides attracted media attention. Rides have continued the last Friday of the month since then, persisting through a Winnipeg winter for the first time.

Background

Critical Mass rides started in San Francisco in 1992. The name is taken from an observation made by bicycle designer George Bliss of how motorists and bicyclists navigate uncontrolled intersections in China: traffic accumulates on the cross street until it has reached a “critical mass,” at which point it is allowed to proceed through.

A promotional motto from other cities is “ride daily, celebrate monthly.” The group is leaderless, with attendees simply showing up at the appointed place and time. Most ride bicycles, but many forms of person-powered transport are represented.

Of primary importance is to remain en masse. Allowing cars to become interspersed with the ride puts participants in danger. This is of particular concern when the mass passes through an intersection and the traffic light changes. One can visualise a long truck passing through the intersection; if it has entered while the light is green, it must continue until it has cleared. To prevent being split up, riders employ a technique called “corking.”

When the mass is traversing an intersection and will not clear it, corkers pull to the sides and stand in front of the stopped traffic of the cross street with their bikes. They often hold signs with messages such as “Thanks for waiting!” and can even hand out flyers or treats. Once the mass has cleared the intersection, corkers join at the back.

At Winnipeg’s ride, the route is chosen on-the-fly. Those at the front discuss which turns to make and the mass proceeds that way. If a participant desires to take a certain course, she can get to the front and make her case. It is empowering to have direct influence in collective action.

Charging Bison Critical Mass

As part of the responses to the military’s Exercise Charging Bison war games that were held in the city in early May, a Critical Mass was held on May 3. While Critical Mass worldwide has no formal ethos or demands, this ride was planned to draw attention to the connection between resource exploitation, war, and consumption.

The ride started from Old Market Square and was quickly descended upon by swarms of police. It became apparent that police were opposed to the corking that keeps the mass together, with some participants being hauled away. Instead, riders decided to proceed slowly so they would never be in the middle of an intersection as the light changed.

The mass proceeded toward the [Charlie Gardiner] Arena, where members of the military were training. There was little police interference, save for when an officer snatched a participant’s flag, amusingly claiming that the staff was sharpened to a point and could be used as a weapon. After a rousing “Legalise flags!” chant it was returned, sans staff, and the ride continued.

Once riders arrived at the arena, they were asked to move onto the sidewalk. They began to comply, but police contradicted themselves and began to apprehend people who were already on the sidewalk! What followed was chaotic, but is unpublishable due to ongoing court proceedings.

May 26, 2006

The events of May 3 were a warning to Critical Mass participants. There was tension before the traditional monthly ride, but also an air of celebration. In recognition of the upcoming Ladyfest Winnipeg, the theme was gender bending. Costumes were common, and spirits were high.

The turnout was much larger than for Charging Bison. Disputes broke out with the police, and they again contradicted themselves and each other, giving out confusing and scattered instructions. Riders were arrested, with allegations of police misconduct coming out in the following days.

Some witnesses and participants filed reports to the Law Enforcement Review Agency, but the lengthy and arduous investigation process has outlasted the will of many.

Response

Critical Mass riders took the unprecedented step of instituting weekly meetings to discuss how to proceed. This is highly unusual, as Critical Mass is more a phenomenon than formal organisation. Several committees were struck to develop a response.

One outcome of the May 26 experience was communication between Critical Mass participants and members of the police force, facilitated by councillor Jenny Gerbasi. This culminated in a meeting at the University of Winnipeg that was documented on video. There were many instances where participants and police representatives did not see eye to eye, but there were some positive signs.

The police in attendance expressed their understanding of the logic of corking, which became important in the coming months. One officer even shared that he has his daughter ride her bike on the sidewalk in recognition of how dangerous it can be on the road with careless drivers.

The June ride was Winnipeg’s biggest, with several hundreds in attendance; an enormous outpouring of support in the face of police repression. The mass was joyful and triumphant, with only a minimal police presence.

The ambulance

Those arriving to Central Park for the July 28 ride were greeted with police who handed out their new policy regarding Critical Mass. They were to take over corking. The mass was to proceed through intersections if the light changed while it was traversing it, as is customary.

The police were inexperienced with corking and attempted to accomplish it with their cars, which are generally not manoeuverable enough to do it well. Still, they insisted that riders not cork.

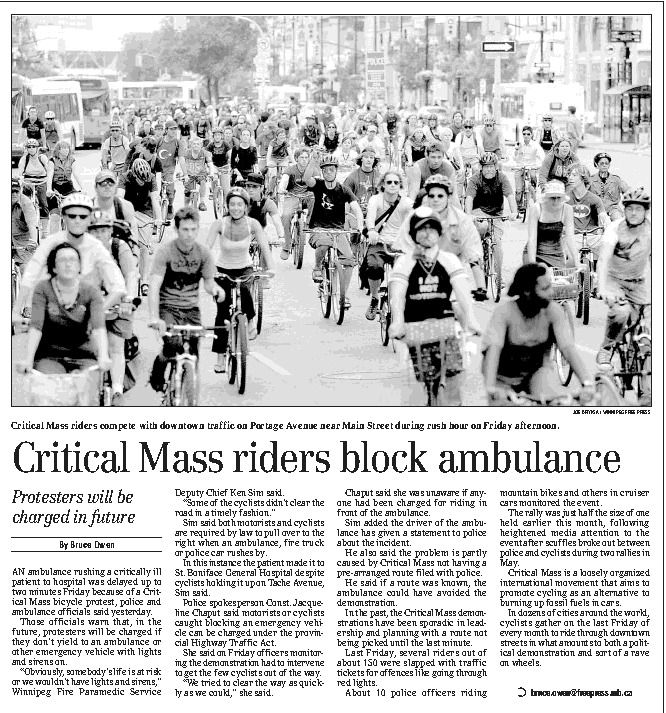

The ride wound its way around downtown before heading over the Provencher Bridge. Riders turned onto Tache, neglecting to consider that it is a direct access to St. Boniface hospital.

As feared, an ambulance was heard approaching. Riders called out “Get off the road!” and within seconds, participants were on the sidewalk on both sides of the road. This quick response lifted many hearts in pride. The ambulance passed and the ride proceeded.

Nothing much was thought until a few days later when a report appeared that the Fire and Paramedic Service charged that Critical Mass had not moved out of the way of the ambulance quickly enough and put the patient in danger.

The smear escalated, with Sam Katz then accusing Critical Mass of having deliberately blocked an emergency vehicle. Participants were upset and insulted, but few media outlets were interested in the truth, preferring to amplify the false allegations. A rider said of that day: “When I looked back, the only people still riding their bikes were the police.” That assessment was confirmed by Uptown reporter Mike Warkentin, whose weblog Tear It Down discusses the misinformation campaign at length.

Waning summer

As the rides continued through the summer, the behaviour of the police became more weighty. They handed out tickets at every opportunity, grinding down the will of those who cannot afford the time and effort it takes to navigate the protracted battles of the legal system. This sapped the joy out of the ride for many, and numbers dwindled.

In the fall, two events grew out of Critical Mass. The first was another group ride called Strength In Power and Numbers, or SPIN, organised by Olympic cyclist Linday Gauld. It was very much like a Critical Mass ride except the route was chosen in advance and it was sanctioned by the police.

The policy committee formed in the June Critical Mass meetings organised a forum for bicyclists called Bike to the Future. Over a hundred cyclists attended, with presentations on bicycle infrastructure in Winnipeg and other Canadian cities and group discussions on how to improve cycling in the city. Bike to the Future has since incorporated and members are eagerly lobbying governments to make cycling a priority.

Winter

Hardy Critical Massers continued to show up for rides on the last Friday of the month through the winter, though attendance dropped to fewer than a dozen some months. The winter rides were spirited and hassle-free.

Another ambulance

The April 2007 ride was a healthy size, but it brought a change in police tactics. They now insisted that the mass not clear an intersection it had already entered, apparently abandoning their July instructions.

As the mass approached the intersection of Portage and Main, the familiar whine of a siren arose. The ambulance was stuck in the rush hour traffic of southbound Main Street, unable to proceed through the gridlock. Riders noted the irony that the cars blocked the ambulance, but no scandalised reports emerged in the media in the days following.

Conclusion

Critical Mass is controversial because it violates the Highway Traffic Act, a car-oriented document that treats cyclists as an afterthought. The Act vaguely admonishes cyclists to ride as close to the curb as “practicable” as well as forbids them to ride in any manner other than single file, but it has next to no laws for drivers that ensure the safety of cyclists. Is it any wonder that we regard the Highway Traffic Act with disdain?

It has been suggested that Critical Mass obtain a permit, but that is untenable. Who, among a leaderless group, would sign for it? What would the route be?

Most importantly: who requests a permit for weekday rush hour or Sunday night cruising? These phenomena are accepted as facts of daily existence. Critical Mass is a monthly celebration of sustainable means of transport that enriches healthy communities.

We live in a culture that fetishises cars to the point that few question that our streets are dominated by vehicles that pollute with toxic gases and obnoxious noises, and periodically take lives. Critical Mass is a response to car culture, a suggestion that there is a better way.